36 years ago, in 1989, Toronto launched its first Fringe Festival. If you’re reading this you’re probably already familiar with Fringe– a celebration of theatre that mounts both award winning and first time productions. The festival has long served as a launch-pad, often showcasing productions that would later be remounted as much larger shows– including Tony award winning musical The Drowsy Chaperone, and the much loved Kim’s Convenience, that would go on to hit Soulpepper’s mainstage during four separate seasons, and eventually become a beloved TV sitcom.

So, during this 2025 Toronto Fringe Festival, I want to share with you someone wonderful who also found one of their first big writing breaks on a Fringe stage.

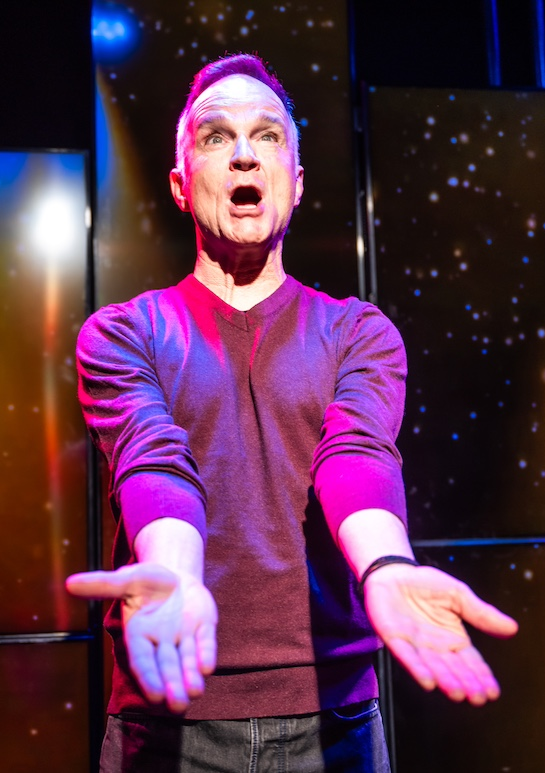

Jonathan Wilson is a Canadian actor, playwright, and comedian, perhaps best known for his play My Own Private Oshawa. The play, a one man show performed as a monologue aboard a GO train, tells the story of Wilson’s childhood as a repressed and closeted gay kid. The show premiered on a Fringe stage during the summer of 1996 and was lauded as one of the festival’s main attractions. My Own Private Oshawa would go on to receive two Dora Mavor Moore award nominations, a film adaptation, and would be called “one of the major hits of the [1996 Fringe] Festival.” by Toronto Star reporter Vit Wagner. Wilson would return to Fringe stages in 2022, starring in Gay for Pay with Blake and Clay, and again in 2023 with the sequel Blake and Clay’s Gay Agenda.

In 2025 I had the opportunity, and the pleasure, of attending Wilson’s autobiographical show: A Public Display of Affection, at Crow’s theatre. Shortly after the show’s closing Wilson was kind enough to sit down with me and my list of burning questions.

Just in case you didn’t get the chance to see A Public Display of Affection, I’ll tell you a little bit about the show.

As an autobiography, A Public Display of Affection is a sharing of the unique and colorful story of Wilson’s life. Where My Own Private Oshawa focuses on Wilson’s childhood, A Public Display of Affection covers the teenage to early adult years. It’s a story of willpower, endurance, relationships and loss. There’s poverty, partying, doing what you must to survive, the onset of the AIDS epidemic, and the connections that held Wilson together through it all.

Emotional throughout, Wilson describes a 1980s Toronto that was anything and everything but kind to Queer people. A few moments in particular had me searching for and squeezing the hand of my partner. I remember the moments after Wilson’s bow, while people began to shuffle out, and I’m stuck in my seat thinking, oh god, I’m so selfishly thankful that someone else fought this battle for me. I’m so happy someone lived this life of strife, rebellion, and suffering so I didn’t have to, so I can live this comparatively privileged life of queer luxury.

Wilson’s performance shows me a mirage of a life I could have lived: closeted, self-hating, scared. I’m one of the lucky ones.

I haven’t been waiting long when he arrives. Jonathan and I exchange first-time greetings and I’m struck with the same realization I have every time I interview an actor. Oh right, I know you, but you don’t know me. It’s a funny feeling.

BadReviews: Once again, congratulations on the immense success of A Public Display of Affection! For those who may not have been able to catch the show, Public Display was about your life, with the bulk of the show taking place in and around 1979. The story is true, the “characters,” your friends, are real people.

Jonathan: Yes, it’s all true; of course you can’t remember every moment, and so you do your best, you give your friends lines based on what you remember, based on the truth of what was said. You know, a lot of those memories are what I call sense memories. Touches, smells, and feelings form a snapshot of a night. Dialogue, or a scene, is distilled down from those memories. Formed from the concentrated essence of the truth.

BadReviews: And so, when it comes to the harder parts, I mean, in the show you describe the passing of a friend, what was it like to write about such an intimate part of your life– their lives too, and even, their deaths? Have you ever felt more “naked” on stage?

Jonathan: It’s certainly one of the most, if not the most, “naked” I’ve been on stage, in the sense that I’ve bared my entire soul. There was another solo show I wrote and performed, My Own Private Oshawa, about being a young closeted gay, and coming out, and how all of that was affected by one of my dearest friends, and that was also a story about a huge piece of my life. A Public Display Of Affection was, maybe, more raw, more honest. Though, it’s funny, about honesty, some people saw the show and thought I overshared a little bit.

Badreviews: I could see how someone might be squeamish when confronted with the full weight of someone’s life.

Jonathan: Right, exactly, and on the contrary, some people also felt I held back too much. Someone told me I was too nice, or I glossed over some of the darkest and grittiest moments. So, there’s really no pleasing everyone. But, you know, I actually performed this show for a group of high school drama students, and it’s interesting to see how today’s youth digests a story from 1979, especially one of this kind.

BadReviews: Right, they may not be familiar with the struggles and violence surrounding queer people in Toronto at that time. The public, even the police, were largely against Queer people. I remember a scene from your show in which people threw things at you during a protest on the street, you were left injured, and an officer largely ignored you.

Jonathan: Yes, and so, some of them told me they appreciated being spared the worst of the details, and some were interested in more of the truth. But I was thankful for both types of reactions, because, either way I got to be a performer, but also a bit of an educator in that moment. I got to say things, teach things, that a teacher can’t necessarily explain in a classroom.

BadReviews: Of course. You can’t teach life out of a text book– this is living history. And, I think a lot of the time it comes down to individual lived experiences for each audience member, and how those experiences can shape how we digest each part of this story.

Jonathan: Exactly, and, funny enough, one student actually told me that the part of the show they found most shocking was when I said I shoplifted.

BadReviews: (Laughing) Oh, that’s what got them?

BadReviews: In the opening of the show, you joked that some people refer to you as a “Queer Elder” now. How does that feel– to be the one some might look to for Queer guidance?

Jonathan: Well, I’m learning to embrace it. I think everyone can feel like a bit of an imposter at times, so I was initially resistant.

BadReviews: What do you think is one of the better pieces of advice you’ve given as a “Queer Elder?”

Jonathan: I’d say as queer people, we’re so often, almost always, in fight or flight mode. Sometimes we assume, or feel like, there are no allies. I’d see this happening, particularly in younger people, and think: who’s going to tell them that we always have allies? Oh, I guess it could be me.

BadReviews: And, to continue that thought, when you see today’s young Queer people, what do you think? Is there something you’re excited to see? Is there something you think we might be a little misguided on?

Jonathan: I’m amazed by the progress the community has made, really. There’s a lot of good. And, of course, there are things that worry me– there always will be, right? My view of Church street is probably jaded by now, but I still visit from time to time. There’s something new happening on every block, but there are also familiar struggles. I did my time in the party culture– back then they called it “party and play,” and I still see the community struggles with addiction, particularly party drugs, and how those drugs still play a big role at a lot of queer events. You know, I’ve lost five friends to party drugs. I know it’s been said before, but, be careful with drugs. That’s my advice to the community.

BadReviews: What part of A Public Display of Affection was hardest to write?

Jonathan: My friend Tommy’s death. I remember, I wrote it alone in a basement, in a sort of solemn way, and when I perform that scene sometimes it still shocks me. Each performance of that scene takes a piece of my soul with it. You know, it’s such an emotional thing to re-live and re-tell, and it’s important to me that that scene exists in the show, but that toll will never go away, and I don’t think I want it to either. I have some friends in opera, and we’ve spoken about this, the way you can connect so deeply with the material you’re going to perform, maybe it makes you weep when you read it, or write it, but you have to master those emotions, and you use those emotions to guide the audience through the story, through those very same feelings, and you allow them to feel what you feel, so that maybe the audience is weeping, instead of you.

BadReviews: You become a conduit for them, to allow them to feel that catharsis that theatre brings.

Jonathan: Oh yes, it is challenging. It can be easier, or harder, on certain days– I lost my sister recently and that really put the show into perspective– the other deaths in the show. After all, in some ways, A Public Display of Affection is about loss, and viewed through that lens, the show can feel a bit incomplete sometimes, because it doesn’t contain all of my loss. But a show can’t be that big. There’s a part of the show where I say the names of people I’ve lost, and once, I did say my sister’s name, and it kind of short circuited my brain right there on stage, and instead of thinking about my next line, I was thinking of her.

BadReviews: My last question: If I gave you the utterly cruel task of condensing your entire show down into one bite sized message, a moral, or a tid-bit of wisdom, in a sentence or two, what do you think it might say?

Jonathan: Well, I’d say to young people: we’ve been through a lot of this before. Certain people will try to fracture the community. They want us to turn against each other, because we’re not as strong apart. It feels dismal to see it replay in real life, but resist. Don’t turn on each other. Your trans family especially, hold them close.

Jonathan Wilson continues to create and inspire on Canadian stages. You can look forward to Wilson’s newest production, spotlighting the short-lived but intense romantic relationship between iconic duo Barbra Streisand and Pierre Trudeau. You’ll also be seeing Wilson in an upcoming cabaret show, before Christmas.